How It Went Down.

I captured a deer poacher one night, caught him red-handed with a dead deer and a rifle. But it didn’t go down the way I had planned it, and it left me feeling sad.

It all started when I heard of an exceptionally large buck deer that was being seen along the Feather River, within a half mile of downtown Oroville, a small town in Northern California. It was a Union Pacific Railroad engineer who first told me about the deer, having spotted it three or four times from freight trains he was running up and down the Feather River Canyon.

Because it was during the fall, about a week before the close of deer season, I knew that the big buck would be tempting bait for outlaw hunters, particularly those who had not yet filled their deer tags. I knew that the deer was too close to town to be legal to hunt and would therefore be relatively safe during daylight hours. But it would be highly vulnerable to poachers at night. I therefore chose to invest some time on the situation.

The area the deer was being seen was a failed housing project. The roads and curbs had been built years earlier, but no houses were ever built. The lots were still untouched oak forest with lots of buck brush and other shrubs that attracted deer. The first night I went there, I drove through the area, shining my roof-mounted spotlight around, and too my vast surprise, I spotted the big buck. He was indeed magnificent, with wide-beamed heavy antlers, four tall, perfect points per side. I drove a couple hundred yards beyond him and backed my patrol rig into the forest, out of sight, to be there should outlaw night hunters come looking for him.

At around midnight, my pulse quickened when I spotted headlights approaching. It appeared to be a pickup with two occupants, and I expected a spotlight to snap on at any second. But it didn’t happen. The vehicle drove on by the meadow where I had seen the buck, and it passed my position without spotting me. Then it drove off the road and into the forest. I heard it stop, and I heard its doors slam and faint voices. Did they intend to hunt the big buck on foot?

I waited for well over a half hour before my curiosity got the best of me. Taking my powerful flashlight, I climbed out of my patrol rig and headed on foot in the direction of the stopped pickup. When I was within 20 yards of it, I could hear low voices. I chose that moment to light up the scene with my flashlight, expecting to see some kind of no good, most likely a drug transaction of some sort. But what I saw was two sparsely clad bodies, one male, one female, reclining on the hood of the pickup.

But I noted something else as well: Apparently, due to the hard, unyielding hood of the pickup, they had built themselves a nest of native vegetation to provide themselves some comfort. Their choice of native vegetation, however, was unfortunate. It was poison oak.

I felt really bad for them, not only because I had ruined there evening, but because I knew well the total misery that almost certainly lay in store for them.

The following night I returned to the area and again backed my patrol rig into the forest. At about 2:00 a.m., headlights appeared, entering the area. The vehicle did not head directly my way, but instead took a different direction. But I could still see it. I expected a spotlight to appear at any second, but no light appeared. Then I realized the driver was illegally using his headlights to sweep the forest for deer. I had no sooner drawn this conclusion when the vehicle stopped, a door opened and a shot rang out.

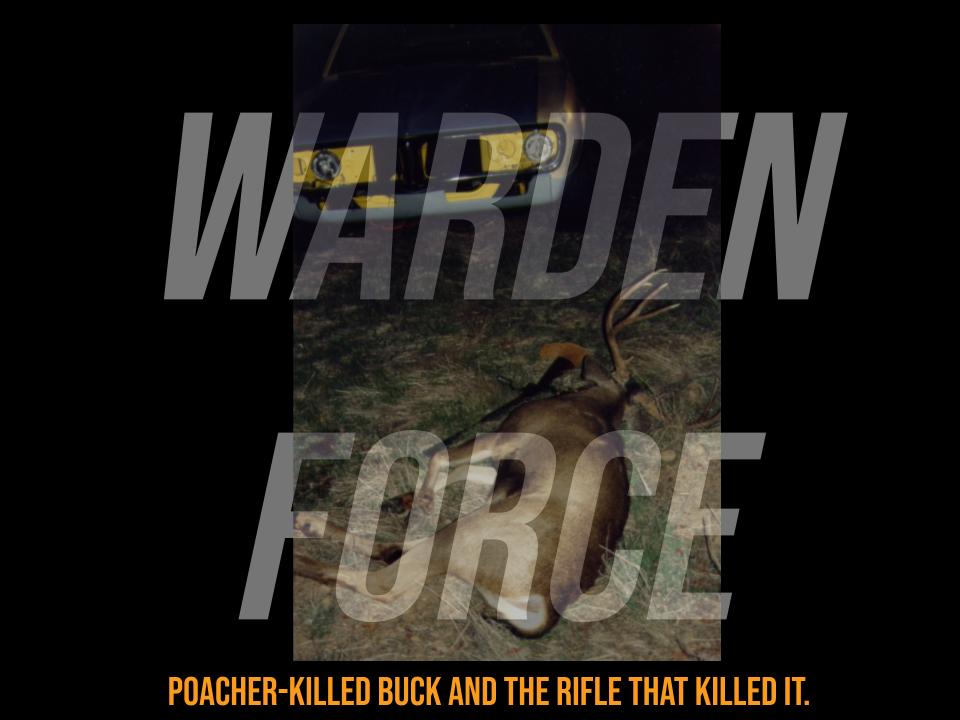

Using no headlights, I drove to the scene and surprised the single suspect, a stunned 19-year-old young man beside a yellow Camero, its engine still running. And there in the car’s headlights lay the lifeless body if the big buck. The suspect was horrified at being caught, far more so than was normal. I soon learned why. He had shot the buck with his father’s rifle, borrowed without permission. The rifle was a beautiful presentation grade Model 94 Winchester, wonderfully engraved with gold inlay. It was, the suspect told me, his father’s most prized possession.

As I issued the citation to the luckless suspect, who was terribly distraught over the pending loss of his father’s rifle, I considered the most likely outcome of his bad judgement. Almost always, in such cases, I and other wardens, seize into evidence the weapons used to kill illegally taken animals. We do this because these weapons are important elements in such cases should they go to trial. And almost always, weapons seized into evidence in such cases are ordered forfeited and destroyed by judges.

With this in mind, and despite the fact that I was regarded by many as a heartless bastard, I yielded to compassion that night and returned the rifle to the grateful young violator. I didn’t expect to run into him again, reasonably certain that he had been forever cured of deer poaching.

But, as I said earlier, the whole incident left me feeling sad. It had been my intention, that night, to save the big buck and get to any spotlighters who might appear before they could shoot. Had the violator used a spotlight, the mere use of which is illegal in California, I could have seen him coming and made a spotlighting arrest before he could spot the deer and shoot. But, as you now know, I failed to anticipate the deer being shot in headlights, without the use of a spotlight. And I feel bad, to this day, about the death of that beautiful buck.